For the 65th year anniversary of Frida Kahlo’s death, who passed away 13th July 1954, we’d like to present an excerpt from the essay “Di Splendente Bellezza. Storie di Corpi e intrecci di sogni” (pages 123-129) on how her self-portraits where a reflection of her physical and psychological condition.

“I’ve always felt drawn to Frida Kahlo‘s tormented story. Even if her image nowadays has become an iconic figure, victim of unscrupulous merchandising and there is little true comprehension of the woman and her extraordinary art, she continues to hold a dear place in my heart. Frida was a woman strong as the roots of a tree, yet emotionally fragile as a dry leaf scattered to the wind.

Her tumultuous and arduous life is reflected in her paintings. Her paintings are also an example for my analysis on jewellery in visual arts as, for those who know the artist well can confirm, she was infatuated with garments and jewellery that were majestic, colourful, original and had a great visual impact. In all the photos that portray her she is always wearing something characteristic, some beautiful traditional dress from her native Mexico. Frida loved dressing up this way to contrast her interior demons, to hide the scars from the accident that not only left her bedridden for years but also caused the amputation of a leg. The artist, who died at a relatively young age, was able (due to her condition) to create a vast quantity of self-portraits, which can be interpreted as real mirrors of the moments she lived and captured on canvas. They can be divided into self-portraits of her whole body, of half-bust or only of her face; all these categories have symbolic attributes within them. Frida always represented herself in the paintings with an impassible expression, as if she were wearing a mask, always the same, imbued with heaviness and nostalgia. In her paintings her gaze is always facing the viewer: in her self-portraits its as if it’s an image of the Self in a mirror; she is looking at the viewer but in truth she is looking in the eyes of the painter, herself.

Her fondness for pre-Columbian or colonial style necklaces dates to the period following her marriage to Diego Rivera, celebrated on August 21st 1929, and attests to the great influence her husband, his political beliefs and his companions (members of the communist Mexican party) had on her. By using traditional clothing, as well as jewellery, Frida manifested her ancestral roots, declaring herself to be a half-breed, a true Mexican born from the union of a spaniard and a native Indios. The artist also chose the background to her paintings following this same criteria, filling them with flora from the region and fauna from the Casa Azul.

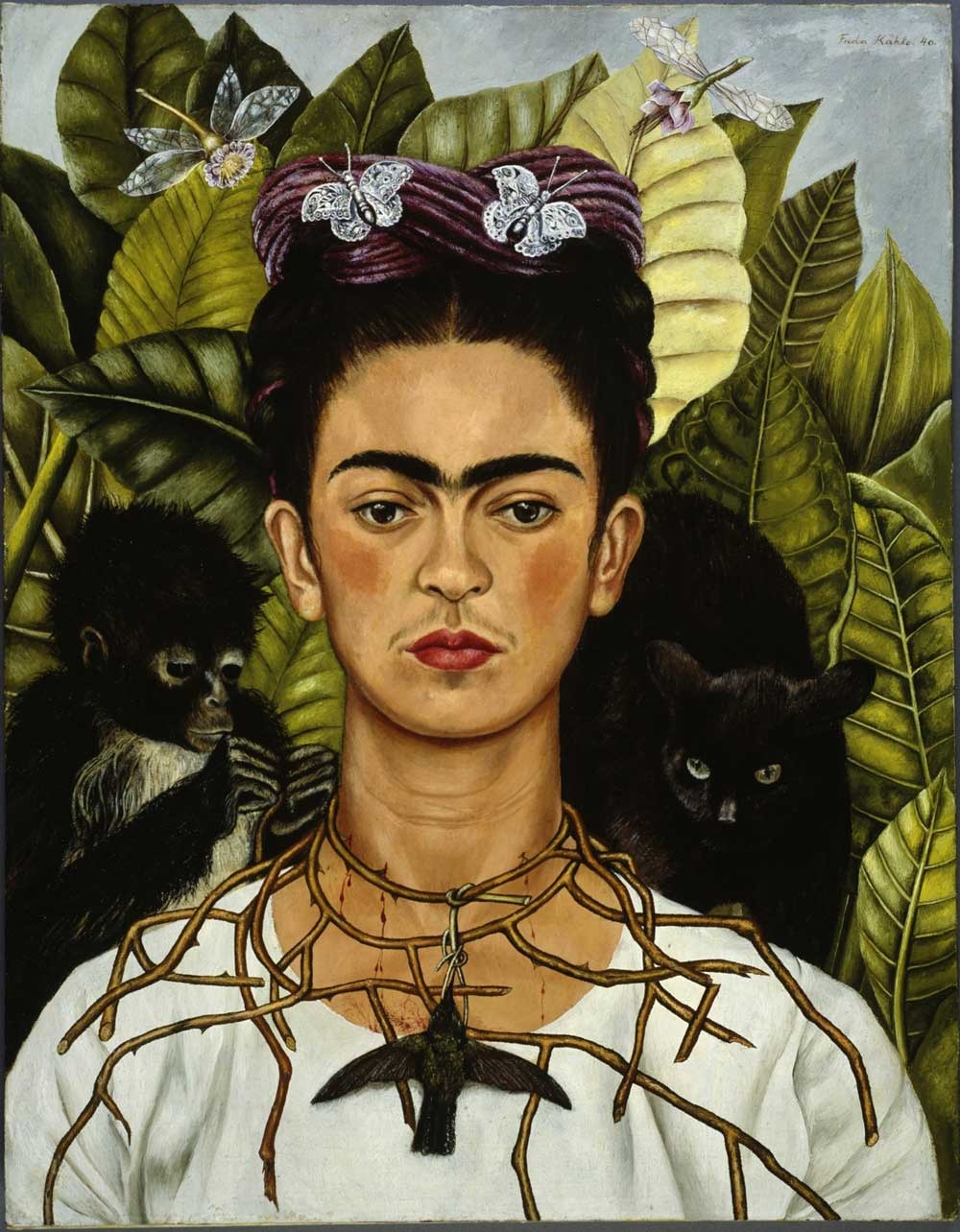

Figure 1 – Frida Kahlo, Self-portrait with Thorn Necklace, 1940, oil on canvas (47 x 61 cm), Harry Ransom Centre, Austin.

The traumas to which she was exposed throughout her life are depicted in her self-portraits: chronologically, in her first paintings there seems to be no evidence of the emotional and psychological tension which starts to appear in her art from the 1930s onwards – from the moment of her accident which caused severe health problems, to the two abortions, one right after the other. As she herself stated, “My subjects have always been my emotions, my mental states and the reactions life caused within me”. Frida’s life radically transforms, but a constant in her self-portraits are the big necklaces and striking earrings she wore with confidence and prowess. There are two instances in which the jewellery becomes something else, both dated 1940, I am referring to Self-portrait with Thorn Necklace and Self-portrait dedicated to Dr. Eloesser (figures 1 and 2). These small paintings are emblematic: there is an absence of beautiful traditional necklaces, replaced here by spiked necklaces spilling blood on the artists’ neck. There is a translation of meaning that coincides with one of the fundamental knots in Frida’s life: in 1940 she marries Diego for the second time but her health conditions deteriorate and she is forced to fly to San Francisco to be treated for spinal pain as well as a fungi infection on her right hand. In the Self-portrait dedicated to Dr. Eloesser, her hand is depicted twice: as an earring, in the same shape Picasso gave to the pendants he gifted her, and as a support for the scroll with the dedication to the doctor who helped treat her.

Figure 2 – Frida Kahlo, Self-portrait dedicated to Dr. Eloesser, 1940, oil on hard fibre (59,5 x 40 cm), Private Collection

This hand/jewellery places the painting in the ex-voto category as it symbolises the healing of the infected hand; the dedication to Dr. Eloesser transforms him into the saint who freed her from pain, suffering and her husband.

So, even though in most of her paintings Frida’s necklaces are synonym of patriotism, of belonging, of identity, here they transform and become synonym of pain, anxiety, prison. This last aspect is visually expressed in Self-portrait with Thorn Necklace, in which her neck is caught in a spiked embrace that seems to both suffocate her and scratch her. And the pendant on the necklace seems to be a dead crow with open wings.

You can see here the strong frontality of the woman, and the similarity of the bird placed on the same axis of her joined eyebrows makes one think of all the times Frida thought about suicide, or of all the times when, exhausted by the suffering of her arduous life, she seemed on the verge of dying. The black bird, or rather the sign the shape of the bird evokes, is like her eyebrows with their distinctive “wing” shape form, imposing itself as on omen of death above her eyes – so expressive and penetrating they seem like the black abyss of her soul.”

[1] The essay, written by Marika J. Farina and curated by Silvia Grandi, is part of the ARTYPE aperture sul contemporaneo collection. It analyses jewellery in it's more profound and significant dimension. Click here to download a free copy of the text.

[2] With reference to A. KETTEMAN, Kahlo, Taschen, 1992.

[3] Critis tend to associate this bird with the Colibrì

Translated by Ludovica Sarti

Read more articles on Focus